In his first few years as a book publisher, Judy offered readers essays, poems and stories based on his war time diaries, sometimes writing under the sly pseudonym of Weimer Port (after a dog breed). Judy’s books supported his belief that the only thing that separated man from dog was the dog’s lack of thumbs and an “alfabet” – Judy loved wordplay and it was evident throughout all his volumes.

But when it came to the world of publishing, the competitive side of Judy’s nature was evident. For those who dared to write about the mighty canine, the Captain was one harsh critic. Judy once boldly proclaimed “[t]here are too many dog books. There are never enuf [enough] good dog books.”

Judy readily took on his competitors in the dog-writing world, noting “[w]e cry out against the flock of volumes on the canine-but our cry only adds to the chorus of barking as much as each author thinks his book is the masterpiece of the pack.”

Captain Judy added to that chorus, becoming a tireless writer of books about dogs, authoring numerous works between the years of 1925 to 1940. Among these titles were technical tomes such as his standard reference work, The Dog Encyclopedia (1925), Kennel Building and Plans (1927), Training the Dog (1927) published in several editions, Principles of Dog Breeding (1930), The Chow Chow: A Complete Presentation of the History, Breeding, Care, Training, Exhibiting, and Selling of this Oriental Breed of Dog (1933), and The Care of the Dog (1940) among them.

But Judy wasn’t always about the dogs, and at times the eclectic author focused on more philosophical projects about the human condition, offering books such as A Soldier’s Diary, Men and Things: Fifty Essays about Human Nature, and The Ways of Men, and Their Private and Public Conduct. Under the pen name, Weimer Port, Judy displayed his affinity for unusual topics with his writing of Chicago the Pagan (1953), and Sayings of Rammikar (1962).

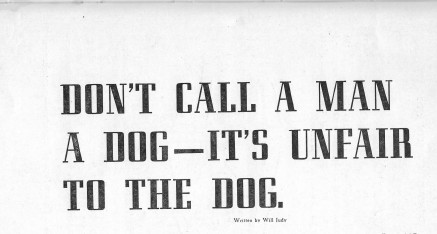

In 1949, Judy presented his most emotional and spiritual tribute to dogs when he wrote and published his eclectic and highly original tome Don’t Call a Man a Dog. With its subtitle, Will Judy’s Scrap Book on Dogs, this work established him as a new breed of dog writer, offering his collective wisdom culled from his years of personal observations and experience.

With the knowledge that the homes of America now contained 15,000,000 dogs, one for each 10 persons, or as Judy put it “every three families owns a dog or is owned by a dog,” the timing of the book’s publishing debut was perfect.

In explaining the significance of the book’s title, Judy stated that “[t]o call a man a dog ever has been a term of reproach even unto insult. This has been true from the earliest centuries. Just what the dog, could he talk, would call some human beings, is a matter of interest.”

The book’s unique focus on the spiritual bond between dog and human found the author using this volume as a virtual pulpit. He preached to modern dog owners who were just beginning to regard dogs as family members; thirsty for knowledge on the proper physical and emotional care of their pets.

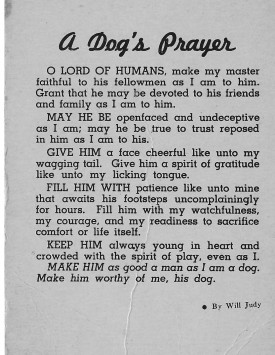

On every page, the sensitive author urged kindness and understanding on the behalf of all dog owners and humans. Judy’s own writings, “Why the World Likes Dogs,” and “A Dog’s Prayer for his Master,” which appear in the book, are moving examples of the special way he had of conveying his feelings, and his ability to connect with others through the written word. In Judy’s unique dog “scrap book,” readers were treated to the serious and silly side of the dog-human relationship. One-hundred black and white photos, clever cartoons, and drawings reinforced his message about the virtues of the dog.

.

As the long term publisher of Dog World, Judy enjoyed an expansive and lucrative venue through which to reach America’s growing population of dog lovers. Under his direction, Dog World went on to be one of the largest and most successful trade publications in pet publishing history.

“Our resolution for the coming year is to give to the Fancy the best that is possible in news and service…As your dog is our dog, no one can kick him without kicking us. With you we pledge ourselves to see that he gets a square deal.” That declaration appeared on the cover of his first issue of Dog World.

The skills Judy acquired in his training for the ministry enabled him to speak with equal ease to those who inhabited the elite circle of the show dog world, those who made their living as dog professionals, and average dog-owners who simply sought sound advice on how to be more responsible guardians to their dogs. All of that for a mere $.20 per issue.

.

Judy wasted no time proclaiming his desire to enhance the quality of life the for the nation’s dogs. He used his position at Dog World to improve conditions for all dogs by advocating the benefits of enlightened dog breeding, and ownership. At the time there were no national standards in the field of breeding. Judy sought to change this and did not allow “low ball prices on stud fees and puppy sales in the magazine’s classified advertising section, establishing a minimum amount of $20 for a stud fee, and $25 for the advertised sale of a puppy.

By 1945, Dog World was in full swing. The popular magazine sold for 25-cents a copy on the newsstand, or received by mail at a rate of $2.00 for a year, $3.00 for two years or the money-saving plan of $5.00 for five years.

In addition to Dog World, a pocket-size magazine called Judy’s was also available. According to a promotional blurb for this publication, “Judy’s represents a new and different type of American journalism-honest thinking, straight talk, and an absence of pretense and hokum.” This publication offered news, articles, literary excerpts and illustrations that focused on “American Viewpoints, and American ways of thot [thought] and life.”

“The Story behind Dog World Magazine,” distributed in October of 1956, had the seasoned editor reflecting on three decades of his publishing experience. “Readers criticize its [the magazine’s] layout…advertisers cheer its results…competitors envy its circulation…and Dog World rolls on each month to an impressive 50,000 circulation,” boasted the proud publisher.

Judy took his publishing responsibilities seriously, but he always maintained a sense of humor and patience while enduring his critics. “Dog World is like the Sears Roebuck catalog…the layouts are lousy-ads, articles, editorials, cartoons, letters all jammed together!” complained one reader. Another carped, “The type’s so small, you can’t read it without a magnifying glass.” Providing a back handed compliment, an overly dedicated woman reader penned, “My husband ‘hates’ me when Dog World arrives, for I hibernate for a full day, reading every word.”

Judy, the globetrotting reporter, enjoyed sharing his escapades from his 28,000 mile dog show circuit from South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Cuba with them. In his “notes to home” style of writing, subscribers learned of his tipping habits and his cocktail of choice, “bourbon straight, a three ounce portion-no ice.”

.

.